5 useful steps to create cooperations between local governments and community organisations

Successful cooperation and the creation of meaningful synergies between local authorities and community organisations is an effective way to improve the quality of life and well-being of local people, while creating new opportunities in the area.

By exploring good practices in several European countries – Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, Portugal and Cyprus – and examining examples that should be avoided, various actions and steps for developing an effective approach to cooperation are summarised in the report “Tools for enhancing cooperation between local governments and community-based youth organisations“. Benefits of strong collaborative practices between local government municipalities and non-governmental organisations are manyfold and well-recognised, and should benefit all involved parties, including community organisations, municipalities, and intermediate organisations.

The report starts by describing the results of a needs analysis to help understand the challenges and needs related to building cooperation between community-based organisations working with young people or aiming to improve young people’s lives and local authorities. Next, the steps to develop a shared vision when forming a partnership are identified.

Five steps to help build meaningful and sustainable cooperations:

- Define and articulate a common outcome

- Establish mutually reinforcing or joint strategies

- Agree on roles and responsibilities

- Establish compatible policies, procedures and other means to operate across organisational boundaries

- Develop mechanisms to monitor, evaluate, and report on results.

Furthermore, local authorities can support NGOs and local social enterprises through financial relationships: funding, grants and subsidies or even through service contracts (public procurement), but also by providing government resources, consulting and other creative ways of cooperation. The report examines the following legal forms of cooperation:

- Public procurement of services

- The municipality provides space and resources

- Project funding

For each of these steps and types of cooperation explanations, suggestions and useful resources to help to prepare for cooperation, as well as examples of partnerships between different organisations are offered.

At the end of the report, potential issues in forming a partnership are discussed, and how to avoid them so that the experience of working together is a positive one for all parties involved.

Read more about cooperation between local authorities and community-based organisations HERE.

The above mentioned outputs were created in the context of the project “Enhancing youth capacity in municipalities and encouraging mutual cooperation using social entrepreneurship as a tool, LOCAL-Y-MPACT” The objective of the project “LOCAL-Y-MPACT” is to strengthen the cooperation between community based youth organisations and social enterprises and local municipalities, and promoting social entrepreneurship as an effective tool for reducing economic inequality, promoting social inclusion and integration, creating resilient society and fostering active participation within local communities.

Toolbox available in:

Greek

Latvian

Lithuanian

Portuguese

Swedish

Key findings about the work integration social enterprises ecosystem in Europe

In the framework of Work Package 1 “Research – State of the Art”, EURICSE made some key findings about the WISEs ecosystem in Europe, labour policies and skills needs and gaps.

The labour market: trends and challenges

Work is crucial to both the welfare of every human being and to the stability of societies. However, unlike the standard assumptions of neoclassical theoretical models, the labour market is far from being perfect. On the one side, there are applicants that are highly qualified and trained, who normally have good career prospects; on the opposite side, are positioned workers that are at risk of labour market exclusion, i.e., workers with support needs (WSN), e.g., people with disabilities (PWDs); people with substance use disorders; convicts and former convicts; long-term unemployed; homeless people; asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants; NEETs; women survivors of violence; members of ethnic minorities and people with low qualifications.

Since their formation, modern welfare states have adopted labour policies to support the work integration of WSNs. These policies can be classified into four main groups: (i) regulatory policies, which consist of the adoption of quota systems that oblige all or some enterprises to hire a minimum percentage of WSNs; (ii) compensation policies, which compensate enterprises for WSNs’ lower productivity; (iii) substitutive policies, aimed at creating a “substitutive labour market”; and (iv) supported employment, which consists of a mix of policies that intervene directly with dedicated tutors to support the selection and training costs of enterprises integrating WSNs.

Nevertheless, most of these policies have proved unable to ensure a balanced allocation of the available labour force. The existence of large groups of unemployed persons who are at risk of social exclusion has encouraged the search for alternative work-integration pathways. Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs) are one of the most innovative and successful examples.

Drawing on a preliminary analysis of WISEs in all the Member States (MSs) of the European Union (EU) and an empirical analysis consisting of both a face-to-face and an online survey carried out in the 13 B-WISE partner countries, the report analyses the main drivers, features and development trends of WISEs in the EU. Furthermore, the report investigates the skills needs and gaps of WISEs’ workers, especially in the digital area.

Work integration Social Enterprises: drivers, features, and models of integration

WISEs are an institutional mechanism of supported employment that favours workers discriminated against by conventional enterprises and provides them with appropriate on-the-job training. Thanks to the expertise accumulated in working with WSNs, WISEs design organisational processes that suit employees’ needs and take stock of their skills and capabilities. WISEs are double-output enterprises; indeed, in addition to trading marketable goods and services, they also deliver work integration support services to WSNs otherwise excluded from the labour market.

In some countries (e.g., France, Greece, and Italy), WISEs have emerged from below, mainly thanks to the self-organisation of supporters, the families of WSNs or WSNs themselves; in other countries (e.g., Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Spain), WISEs have evolved from traditional sheltered workshops, which have progressively shifted to a more entrepreneurial stance and started to behave more and more like WISEs.

Since their emergence, WISEs have developed different models of integration. While some WISEs are structured to create stable job positions for WSNs within the organisation itself (permanent integration model), some other WISEs train WSNs on the job to prepare them to work in the mainstream labour market (transitional integration model). A third group of WISEs have developed a mixed integration model. Several factors explain the choice of a particular model of integration, including the types of WSNs integrated, the incentives and constraints of public policies, the connections of WISEs with labour policies and the degree of interaction of WISEs with other potential employers.

WISEs operate in a wide spectrum of economic sectors. The lion’s share are however labour-intensive industries (e.g., manufacturing, construction, cleaning) where low added-value jobs predominate, requiring low levels of specialization from the workers’ side.

WISE recognition

The report maps the legal structures of both legally recognised WISEs and WISEs that operate “outside the radar”, as they are neither legally defined as WISEs, nor conceived as WISEs by the organizations themselves.

WISEs vary to a great extent across EU in terms of legislation: while in some countries (e.g., Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain) WISEs have a specific legal framework that applies to them, in other countries (e.g., Austria, Estonia, Ireland, Netherlands and Sweden) WISEs mainly use traditional legal forms that were neither specifically designed for them, nor for social enterprises whatsoever. There are moreover countries (e.g., Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Luxembourg, Poland, Romania and Slovakia) where the ad hoc legislation for WISEs introduced are rather ineffective and the newly established WISEs continue to use legal forms that have not been designed for them. In some countries, WISEs are registered in special registers (e.g., in Sweden) or are identifiable thanks to specific funding schemes (e.g., in Austria) or private mark (e.g., in the Netherlands).

Noteworthy is that in countries such as e.g., Italy, changes in legislation have been either essential or key in fostering the development of WISEs on a wide scale. Finally, in countries (e.g., Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Spain) where sheltered workshops have transformed into fully-fledged enterprises, WISEs use legal forms or statuses that were originally designed for the former.

WISE resources

Running a WISE entails higher production costs (mainly related to the training and supervision of WSNs integrated) when compared to conventional enterprises. WISEs struggle moreover to access repayable resources owing to their specific not-for-profit nature. For these reasons, WISEs have developed peculiar models of sustainability and rely upon a mix of public and private resources, including non-monetary contributions (e.g., voluntary contributions, donations received from members and assets made available by the community); non-repayable resources (public – e.g., subsidies and grants to cover investments in fixed assets, support for workplace adaptation and training – and private, e.g., indivisible reserves resulting from the constraint on the distribution of profits); repayable resources (from e.g., socially-oriented and ethical banks); fiscal advantages and resources from income generating activities thanks to the selling of goods and services to public agencies, individuals, and conventional enterprises.

As highlighted by the B-WISE research, there is overall a need for more enabling public schemes and policies. The great majority of EU MSs have indeed inconsistent and fragmented public support systems, which fail to consider adequately the social responsibility taken on by WISEs. In more than a few countries, there is disproportionate access to public support resources – which depends on the target groups addressed by WISEs – with WISEs integrating PWDs having access to a more generous support system. In other countries, only selected typologies of WISEs benefit from a targeted support system, whereas the remaining typologies have no access to support measures whatsoever.

Country patterns: from traditional labour policies to WISEs

WISEs can be clustered in three groups of countries: (i) Central and Eastern Europe (i.e., Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Poland, Romania and Slovenia), (ii) Southern Europe (i.e., Greece, Italy and Spain) and (iii) Western Europe (i.e., Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands).

In Central and Eastern Europe WISEs are the most widely recognized social enterprise typology. In these countries, WISEs legal recognition and public support are relatively unsatisfactory, whereas the EU has played a major role in supporting their development.

In Southern Europe, WISEs are strongly rooted in the longstanding tradition of cooperatives and they have been legally recognized. Key challenges influencing the development of WISEs include high unemployment rates, the presence of a large informal sector, a high segmentation of the labour market and a poor development of active labour market policies.

In Western Europe, active labour market policies are well developed; they have on the one hand contributed to higher employment rate and, on the other hand, they have led to more flexible labour markets. While WISEs are fully integrated in the welfare system in Austria and Belgium, they are treated like any other enterprise in the Netherlands, where an “equal playing field for all enterprises” exists.

Technical and soft skills in WISEs

The aim of the B-WISE face-to-face empirical analysis was to identify skills needs and gaps of three target groups: (i) enablers (e.g., manager, area coordinators, and ICT specialists); (ii) supporters (e.g., job coaches, tutors and mentors) and (iii) WSNs. Drawing on the European Skills, Competences, Qualification and Occupations (ESCO) framework, 403 workers were interviewed so as to examine their skills endowments and gaps.

Based on the research conducted, to perform their jobs, enablers require a broad spectrum of managerial as well as communication, collaboration and creativity-related skills. Supporters – who deal with a variety of activities, from planning work time and space to assist WSNs – need a mix of both hard and soft skills. In their view, the most relevant skills are those related to the training and support of WSNs. Lastly, according to WSNs, operational skills – such as sorting and packaging goods, cleaning and assembling products – are essential to carry out day-to-day activities with accuracy, precision and autonomy.

While there is no significant gap between skills relevance and skills endowment, there is room for improvement for all the three target groups, especially in those skills that are considered as most relevant. According to both enablers and supporters, skills gaps are mainly due to the lack of economic resources. Based on enablers’ responses, also labour shortages of workers with the needed job profile have however a role in explaining their own skills gaps. Supporters consider by contrast the scarcity of suitable training activities a key explaining factor. Lastly, WSNs identify the lack of time to learn new skills as the most relevant reason explaining their own skill gaps.

Enablers’ and supporters’ skills gaps negatively affect their capacity to assist current or additional WSNs in their work integration paths. The main concern for WSNs is their inability to work while ensuring proper quality and/or speed, which may provoke delays or hamper the quality of the products/services supplied to customers. Training is seen as the most important measure to address skills gaps, but the lack of resources to be allocated to training by most WISEs hinders training attendance. On top of this, respondents highlight the lack of suitable training activities that are fully tailored to address the skills gaps especially of WSNs.

Technology and digital skills gaps in WISEs

Relying on both the findings of the face-to-face and online survey (completed by 175 enablers), the study shows how technologies and digitisation processes are – especially in large WISEs, in which the level of digitization is higher compared with smaller ones – applied to a large extent in management process (through e.g., the use of cloud computing services and e-invoices) and for the standardization of production processes (through e.g., technologies like Enterprise Resource Planning software packages). Conversely, some advance technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, rapid prototyping and assistive technologies are considered less relevant.

For what specifically concerns digital skills, there are no significant discrepancies between the relevance of digital skills and their level of endowment for the three target groups. Enablers are the category of WISE workers who most need these skills. On the contrary, WSNs require little digital skills to carry out their work activities and digital skills seem to be more relevant in their private life activities rather than at work.

As for technical and soft skills, there is room for improvement of digital skills for the three target groups. However, a difficulty in finding training initiatives for bridging these gaps has been detected, especially for WSNs.

Development trends and challenges

In all the countries where they operate, WISEs have demonstrated their ability to tackle key problems of labour exclusion affecting contemporary economies that traditional labour market policies had proved unable to tackle. In spite of their success, WISEs potential is still far from being harnessed.

WISE visibility has increased significantly over the past decades and new laws recognizing WISEs – especially via legal statuses – have been adopted in a growing number of EU MSs. Noteworthy is also the trend of recognising WISEs via cooperative legislation adjustment, which is diffused in countries distinguished by a longstanding cooperative tradition.

The scarce development of ex lege WISEs in some countries can be traced back to two main factors: the insufficient degree of engagement of WISEs in law-making processes and the policy-makers’ incapacity to identify all types of organizations that may be considered WISEs.

All in all, there is a trend towards the broadening of WISEs target groups: in the past, PWDs were the only group conceived as disadvantaged while in more recent times, the concept of disadvantage has been progressively enlarged so as to include a broader set of vulnerable workers.

Another key trend development detected is that, over the past decade, the domains of engagement of WISEs have progressively broadened towards fields – such as those related to ICT, culture and the management of cultural heritage – with a higher added value.

Analysis confirms however that to fully exploit the added value of WISEs, a more enabling environment is needed. In particular, there is a need for more enabling public schemes and policies. New market access opportunities for WISEs are nevertheless emerging from the 2014 EU Directives on public procurement.

Innovative strategies are being moreover experimented by some WISEs with a view to improve their integration capacity. Among the most innovative, collaborations between WISEs and conventional enterprises are becoming a widespread strategy in some countries also as part of particular legal and/or policy schemes, such as quota systems. Worth mentioning is also the tendency to build networks that group WISEs together.

When it comes to skills development, WISEs face specific challenges. The level of skills endowment of the three groups of workers targeted by the empirical analysis seems to be rather good. However, data show that there is substantial room for improvement and failure to fill these skills gaps could jeopardize WISEs’ capacity to assist current and/or new WSNs. Training activities are considered particularly important, but the lack of time and resources – especially in small WISEs – to be allocated to training hinders training attendance. As regards specifically WSNs, targeted training, planned on the basis of their needs and capabilities, is needed.

Considering digital skills, results show that there are no significant discrepancies between their relevance and the level of endowment for the three target groups. Worth noting is that for WSNs specifically, digital skills seem to acquire a higher relevance in private life activities compared with work activities.

Another important tendency emerged is that the level of digitization is higher in larger WISEs. However, technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, rapid prototyping and assistive technology are considered as less relevant and therefore are rarely used within WISEs. Nevertheless, those are important technologies, mainly for the adaptation of WSNs’ individual workplaces, and their potential should be fully-exploited by WISEs.

The B-WISE project, Blueprint for Sectoral Cooperation on Skills in Work Integration Social Enterprises, is an Erasmus + project coordinated by EASPD with the support of ENSIE.

What are the skills needed for work integration social enterprises' workers?

Various skills are needed for WISEs workers (enablers, managers and workers with support needs), here are the highlights of the report.

One of the research activities led in the framework of work package 1 was to map skills needs and gaps in WISEs across the 13 project partner countries. It was led in the form of an empirical analysis to map the skills needed to perform the jobs and fill the skills gaps in WISEs, with a view to profiling the training requirements of three main professional profiles, namely “enablers” (e.g., managers, area coordinators, IT specialists ); “supporters” (e.g., job coaches, tutors, and mentors) and and workers with support needs (WSNs)*. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 403 persons (89 enablers, 145 supporters, and 169 WSNs) from a sample of around 100 WISEs in 13 countries across the EU. The investigation analyzed the available skills deemed as the most relevant for the above mentioned categories of workers and skills gaps. In addition, the reasons for such skills gaps, their effects on WISEs, and the strategies put in place to cope with them were examined.

The skills needs and skills gaps analysis highlighted four key findings.

First, the survey showcased that WISEs face specific challenges when compared to conventional companies. The level of skills endowment of all three respondent groups was rather good, with enablers and supporters particularly well aware of the broad set of skills needed to work in WISEs. The data analysis did not highlight any significant difference across countries, but it confirmed there is substantial room for improvement. Failing to fill skills gaps is regarded as particularly risky since it could jeopardize WISEs’ capacity to assist current and/or new WSNs and lead to an increased workload for staff. In other words, skills gaps could hinder the process of work integration.

Second, the various groups of respondents chose specific skills as particularly relevant. Enablers rated management skills as highly important: from designing strategies for the development of WISEs and making decisions to engaging in direct relations with employees to coordinate their activities and motivate them. Among other skills, negotiating with clients, especially private ones, was perceived as highly relevant. Supporters pointed out the multifaceted nature of work as they deal with a variety of activities, including planning work time and space, assisting and supporting WSNs in carrying out their tasks, and managing and reporting activities to their supervisors and coordinators. A mix of hard and soft skills is required, the balance of which also varies according to the specific role assumed by a supporter within an organization. However, what clearly emerged is that “assisting workers with support needs for their job” is crucial when looking at supporters. Interviews highlighted that counseling and mentoring activities, in some cases, aim to stimulate workers in their own growth at work: they favor a positive atmosphere and even touch on some personal aspects that impact work. Some interviewees felt that they have received all the necessary tools to manage the support and counseling of WSNs. There were cases in which a lack of training related to psychological aspects of the job, as well as the diverse typologies of workers’ disabilities, influenced the effectiveness of supporters’ activities. Finally, “collaborative, communicative and operational skills” were essential for WSNs to carry out day-to-day work activities with accuracy, precision, and autonomy. The importance of specific skills depended on the type of economic activity carried out, which in the sample interviewed ranged from manufacturing to administrative/office activities, catering, and waste management.

Third, when looking at enablers’ skills, the age of the organization makes a difference. Start-up WISEs need to build new skills to recruit the most suitable staff and develop effective working teams, while in more structured WISEs, the development of organizational and decision-making strategies comes to the fore.

Finally, from a comparative viewpoint, all three respondent groups considered specialized technical knowledge related to media and technology as not relevant; this can be traced back to the key role played by soft skills and other technical knowledge necessary to assist workers in carrying out their job tasks in WISEs.

Against the background of addressing skills gaps, respondents consider training activities particularly important. Based on their answers, training is primarily financed by WISEs’ own resources: most WISEs provide for training internally or support employees’ participation in external training.

Looking at the reasons behind skills gaps, enablers and supporters expressed similar opinions by identifying the shortage of economic resources as a very important factor and the lack of motivation as the least relevant reason. To tackle the scarcity of resources, one strategy is to support WISEs’ access to private funding schemes by encouraging their desire for collaboration via mutually supportive mechanisms.

An additional obstacle to filling skills gaps is the lack of time, which is typically a barrier in relation to training activities in small organizations. WISEs, especially when they are small in size, struggle to detach personnel from their required work activities. In these situations, training carried out within the organizations and combining both theoretical and practical activities can help WISEs overcome this problem.

Moreover, according to respondents, it is particularly difficult to identify the optimal training activities to improve supporters’ and WSNs’ abilities. Indeed, training activities may be stressful, especially for WSNs, when they are not fully tailored to address their specific skills gaps. Thus, it is important to invest time and energy in adapting training and education to the specific needs of recipients. Hence, individualized and targeted training designed and planned based on workers’ real needs and capabilities is crucial.

Finally, the findings of the survey underline the importance of further research on both the content and modalities of training., which will be done later in the B-WISE project.

Read the full report HERE.

The B-WISE project, Blueprint for Sectoral Cooperation on Skills in Work Integration Social Enterprises, is an Erasmus + project coordinated by EASPD with the support of ENSIE.

* E.g., people with physical and/or sensory disabilities; people with intellectual and/or learning disabilities; people with psycho-social disabilities and/or mental illness; people with substance use disorders; convicts and ex-convicts; people on long-term unemployment; homeless people; asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants; NEETs; female survivors of violence and members of ethnic minorities.

Technology and digital skills gaps in work integration social enterprises

This article focuses on technology, digitisation and digital skills of WISEs in the 13 B-WISE participating countries. It summarises the results of 403 face-to-face and 175 online surveys carried out between October and December 2021. For a more comprehensive report (English), please consult chapter 7 of the “Report on trends and challenges for work integration social enterprises (WISEs) in Europe. Current situation of skills gaps, especially in the digital area.“

Relevance of technology and digitisation for WISEs

Based on the surveys filled out by enablers (e.g., manager, area coordinators, and ICT specialists) we can state that:

- The digitisation of management processes (e.g. cloud computing services and e-invoicing) is the most significant domain in which WISEs apply technologies and digitisation processes.

- The second important domain is the digitisation of standardised production processes (e.g. ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) software packages).

- In addition, the technological adaptation of individual workplaces is considered less relevant today and in the future.

- Artificial Intelligence (including big data and Internet of Things), rapid prototyping and assistive technologies are rarely used.

- Large WISEs reach in almost all cases a higher level of digitisation. As a consequence, scale will be an important factor for WISEs if they want to take further steps towards digitisation and towards the implementation of technologies.

Enablers: relevance of digital skills, needs and gaps

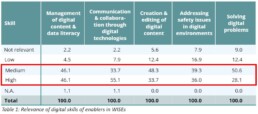

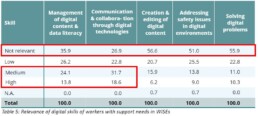

In the face-to-face survey targeting enablers, the relevance and the level of endowment of digital skills of the enablers in their WISE (their own digital skills and those of colleagues with a similar role) were questioned. Five competence areas were investigated in this survey: (i) management of digital content and data literacy; (ii) communication and collaboration through digital technologies; (iii) creation and editing of digital content; (iv) addressing safety issues in digital environments; and (v) solving digital problems. The survey shows following results:

- No significant discrepancies between the relevance of digital skills for enablers (upper table) and the level of endowment (lower table).

- According to enablers, all competence areas are relevant for enablers.

- This goes together with the level of endowment.

Supporters: relevance of digital skills, needs and gaps

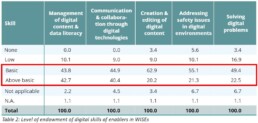

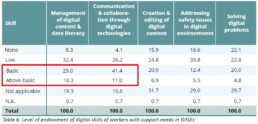

To get a clear impression of the digital skills of supporters (e.g. job coaches, trainers), the survey for enablers included a judgement on the relevance and the level of endowment of the digital skills of the supporters in their WISE. The survey shows following results:

- According to enablers, following competence areas are most relevant for supporters:

- management of digital content and data literacy;

- communication and collaboration through digital technologies.

- According to enablers, 9.7% of supporters have no digital skills, 24.7% have a low level, 30.4% a basic level and 22% an above basic level of digital skills.

- For the two competence areas considered as most relevant for supporters, over 60% of supporters have a level of endowment that is basic or above basic (no significant discrepancies between relevance and level of endowment).

Moreover, the face-to-face survey addressed to supporters included a self-assessment, collecting information on the use of digital skills at work and at home. Supporters were asked if they performed a certain action (at work or at home) during the last three months. The self-assessment covered six categories: information skills, communication skills, problem-solving skills (A “Basic” and B “Advanced”), and software skills for content manipulation (A and B). Based on the survey results, we can state that:

- Supporters use and need digital skills both at work and at home.

- Although the use and importance of digital skills at work is high, supporters use more digital skills at home.

- Only basic and advanced software skills for content manipulation (e.g. word processing software, spreadsheet software or software to edit photos, videos or audio files) are more frequently applied at work.

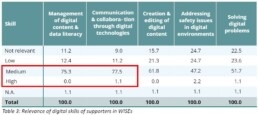

Workers with support needs: relevance of digital skills, needs and gaps

To map the digital skills of workers with support needs, the survey addressed to supporters included a judgement on the relevance and the level of endowment of the digital skills of the supporters in their WISE. The survey shows following results:

- Overall, according to supporters, digital skills are not very relevant for workers with support needs at work.

- According to supporters, following competence areas are most relevant for workers with support needs:

- management of digital content and data literacy;

- communication and collaboration through digital technologies.

- According to supporters, 13.8% of workers with support needs have no digital skills, 28% a low level, 24.6% a basic level and 7.7% an above basic level of digital skills.

- According to supporters, there are no significant digital skills gaps among workers with support needs: relevance and level of endowment go hand in hand.

The face-to-face survey addressed to workers with support needs included the same self-assessment as the one inserted in the survey targeting supporters, covering the same six categories of digital skills. Workers with support needs were asked if they performed a certain action (at work or at home) during the last three months. Based on the survey results, we can state that, overall, workers with support needs use significantly fewer digital skills at work than at home.

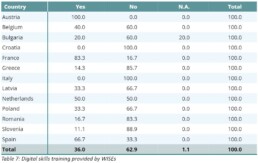

Digital skills training

- Most WISEs interviewed do not provide training on digital skills themselves. Nevertheless, there are some exceptions: more than 50% of the WISEs interviewed in Austria, France, Spain and the Netherlands organise training on digital skills themselves.

- The larger the WISEs, the more likely they will provide training on digital skills.

- Among the three target groups, the main beneficiaries of training initiatives on digital skills are enablers, while the participation of workers with support needs in training activities aimed at improving their proficiency on digital skills is lower.

- The fact that the level of endowment of digital skills is high for enablers shows that the current training initiatives meet their needs.

- Overall, a limited share of the WISEs interviewed (16.9%) have established partnerships with other local/regional organisations to promote external training initiatives for WSNs.

Relevance of digital skills, needs, gaps and training: conclusions

- Considering digital skills, there are no significant discrepancies between the relevance of digital skills and the level of endowment for the three target groups.

- Enablers need most digital skills at work, consequently there are more training initiatives targeting enablers. These initiatives meet the needs of enablers, given that their level of endowment of digital skills matches the relevance of the skills.

- Supporters need digital skills to a certain level and their level of endowment is considered basic or above basic for the skills they need most.

- Finally, it can be noted that workers with support needs require little digital skills at work, this also matches with their level of endowment. Moreover, there are little training initiatives for workers with support needs. The workers do not need digital skills at work, but the self-assessment shows that they do use digital skills at home. This raises the questions if WISEs should pay more attention to the need for digital skills in other contexts, outside of the working environment.

The B-WISE project, Blueprint for Sectoral Cooperation on Skills in Work Integration Social Enterprises, is an Erasmus + project coordinated by EASPD with the support of ENSIE.

Social Entrepreneurs for Tourism

The field of social entrepreneurship is on the rise, drawing more supporters and venturing into diverse sectors. To keep the trend up, addressing challenges posed by COVID-19 with innovative solutions had become essential. One such strategy involves social enterprises not only sticking to their core business but also reshaping and adapting their offerings to cater to the tourism industry. This dual-purpose approach aims to not only generate additional income but also ensure the sustainability of these enterprises in the face of evolving circumstances.

The Latvian Social Entrepreneurship Association, in cooperation with the Georgian Social Enterprise Alliance (SEA) and the Regional Sustainable Development Institute (RSDI) of Georgia, had been exploring opportunities to promote the possibility of social entrepreneurs engaging in the tourism industry under the project “Social Entrepreneurs for Tourism” funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia.

Social entrepreneurs face several challenges when stepping into the tourism sector. The lack of information on current tourism trends, along with the need for innovative service development and entrepreneurial skills, makes it difficult for them to integrate successfully. The Covid-19 crisis hit the tourism industry hard, prompting shifts in habits and industry dynamics. Travelers now lean towards exploring local destinations, engaging in traditional events, and supporting small businesses. To ensure a sustainable and engaging tourism experience that positively impacts communities, successful collaboration is crucial. This collaboration should involve various stakeholders, including public and private organizations, local producers, social entrepreneurs, cultural sectors, local authorities, and tourism management organizations. By fostering cooperation among these parties, we can, and indeed did, craft a tourism offer that aligns with evolving preferences and creates a positive social footprint in the visited communities.

The project successfully unfolded from July 1, 2022, to November 15, 2022, with the overarching goal of nurturing the social business ecosystem and fostering a positive social impact in Georgia. During its implementation, small and medium-sized social enterprises were empowered to adapt their services to thrive in the tourism industry. The key achievements include:

- Identification of social enterprises adept at providing services in the tourism sector.

- Enhancement of capabilities, knowledge, and skills for social enterprises, NGOs, and civil society organizations, enabling them to deliver high-quality tourism services and collaborate effectively with tourism agencies.

- Support provided to tourism sector representatives and fellow social entrepreneurs in overcoming the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic through innovative approaches.

- Creation of opportunities for cooperation, meetings, and networking among social entrepreneurs, promoting the exchange of experiences and knowledge.

Within the framework of the project, social entrepreneurs capable of providing services in the tourism industry were identified. They became acquainted with existing and potential social business initiatives in the field of tourism, including those already offering various activities and those with the potential to be involved in this field. The capacity of social entrepreneurs was strengthened, with efforts directed towards improving their knowledge and skills to develop activities in the tourism sector. Experience exchange and individual mentoring were provided to aid in the development and enhancement of products/services.

During the project, we developed and tested tourist routes in different regions of Georgia, which underwent multiple improvements and refinements. These routes involve the social enterprises that we have been working with along the way and offer an experience that brings a positive impact. To explore more about routes alongside detailed offers from social enterprises check out our article or download the Touristic Catalog of Social Enterprises.

The project extended to the exploration of the relationship between social tourism and social entrepreneurship in Latvia. While the concept of social tourism has been widely discussed since 2014, its actual presence still has significant room for growth. In Latvia, social enterprises have embraced the concept in their business practices, which is not surprising given the close alignment of core values between social tourism and social entrepreneurship. If you’re interested in further details, the article on Social Tourism Development in Latvia provides insights into the recovery efforts amidst the COVID-19 crisis. This article sheds light on how these intertwined concepts have played a role in navigating the challenges posed by the pandemic and fostering resilience in the community.

The entire journey facilitated the sharing of experiences, networking, and learning from successful examples. The project produced tangible resources, including a touristic catalog, and laid the groundwork for participant enterprises to sustain their development in the social tourism sector. As a result, these efforts have collectively contributed to the growth and advancement of social entrepreneurship in Georgia’s tourism industry.

This piece was written in the framework of the project “Social Entrepreneurs for Tourism”, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia.

Impact Management Toolbox

This toolbox helps you plan, implement and communicate the positive changes that you aim to create with your initiative or organisation in the lives of young people.

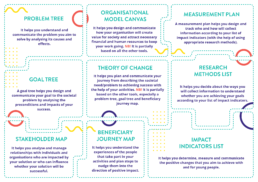

What? A combination of nine tools especially developed for planning, measuring and increasing positive impacts of the organisations and reducing any negative effects of their activities.

For whom? For you. If you are active in an organisation that works with and for the young people. For example, youth associations aiming to develop their members or social enterprises providing services to youngsters.

What if I don’t work with young people? The tools will be absolutely suitable for designing and measuring the impact of your activities too! However, all the examples in this toolbox are related to young people as they are the main target group here.

By whom? Top organisations developing social impact measurement, youth field and social entrepreneurship in the Baltic States. For more information, see below.

Who financed? The project “BALTIC: YOUTH: IMPACT” has been co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union.

With the help of this toolbox, you can be even more successful in your activities!

If you are reading this, you are probably active in an organisation that aims to create a positive impact in the lives of young people.

Perhaps you want to unleash the creative potential of youngsters… or help young people who have had lesser opportunities compared with their peers…. or provide valuable knowledge and skills to the members of a youth organisation.

The toolbox has been designed to help you plan, do, measure, improve your activities… and repeat! In other words – you will be able to create a more positive impact with your activities.

You will have more clarity and make better choices.

Also, you will be more effective in involving your team and explaining your work outside the organisation.

In conclusion, you will be able to leave a legacy that you can be proud of!

Feel free to try out and use just one, several or even all of the tools!

You can take an ambitious journey covering all the tools to get your organisation’s impact management to a new much higher level. In that case, start from the problem tree, then move on to the next tools and complete your development process with the organisational model canvas.

Alternatively, you can choose a tool that seems to match your current needs the best. For example, if you feel that you need to understand better how to attract young people and keep them involved at different stages of your activities to achieve a bigger impact, you should start with filling in the beneficiary journey map.

You can find brief descriptions of each of the tools in the toolbox here.

How this toolbox has been created?

The toolbox has been developed based on its creators´ experience of what is needed to increase the positive impact of the organisations that work with young people.

The Erasmus+ project “BALTIC: YOUTH: IMPACT” enabled the top organisations developing social impact measurement, youth field and social entrepreneurship in the Baltic States to come together and create this toolbox. The lead partner in developing the tools was Stories For Impact while all the other partners contributed with their ideas and experiences, including the testing of the tools.

We have taken into account:

- the previous materials developed by other experts for the same or similar purposes,

- our project partners´ own practical experience of training and consulting the youth organisations.

The exact structure and design of the tools have been created specifically within the project “BALTIC: YOUTH: IMPACT” as a result of testing the preceding tools and developing them further. Usually, we developed the earlier tools by simplifying these to make it easier for you to try out and use them.

What about the sources of impact planning and measurement tools?

Many of the tools included in this Toolbox have been in use already for a few decades. For example, UNDP´s publication “Handbook on Planning, Monitoring and Evaluating for Development Results” introduced a problem tree – the very first tool in our Toolbox – to global audiences already in 2009. The theory of change tool was invented and promoted even earlier, in the 1990s. So far, among the best compilations of these tools is a handbook “Maximise Your Impact – A Guide for Social Entrepreneurs” (2017).

As the mentioned tools have become common knowledge among the professionals who practice impact measurement and service design, no specific additional references have been made (with a few exceptions) within the toolbox.

We have combined different versions of the tools and developed them into formats that we think are super useful. You are welcome to take these tools, develop them further and share the results with others too.

What about the sources of service design tools?

Service design is a process for creating experiences and solutions that work for the customers and other people involved.

It’s a human-centred approach with an end goal of suiting all users’ needs while keeping in mind the big picture. The authors of “This is Service Design Thinking” have stated five key principles that should be followed for good service design: user-centred, co-creative, sequencing, evidencing and holistic.

Many different tools have been developed to bring the idea of service design into reality. They have been modified and perfected over the years, so it’s hard to point out an author for each tool. Therefore, it is generally agreed that they don’t need to be credited.

You can find a wide range of service design tools on this link but they can be a bit too generic for your specific purposes. So, we have picked out a “Stakeholder Map” and “Beneficiary Journey Map” and will walk you through them in a way that’s most beneficial for youth organizations. Service design for you can be different from that of for-profit companies that these tools were initially created for.

What about the source of the Organisational Model Canvas tool?

Another commonly used framework that we have modified further is the business model canvas – originally a tool with nine boxes for developing new business models, as well as analyzing existing ones.

The framework was first introduced by Alexander Osterwalder in 2005, published in a book by him in 2008 and altered by different authors ever since.

We’ve modified developed it into a tool called “Organisational Model Canvas” so that its brilliantly useful approach could also be successfully used by a youth organization or a social enterprise.

Impact Management Toolbox has been prepared and tested by:

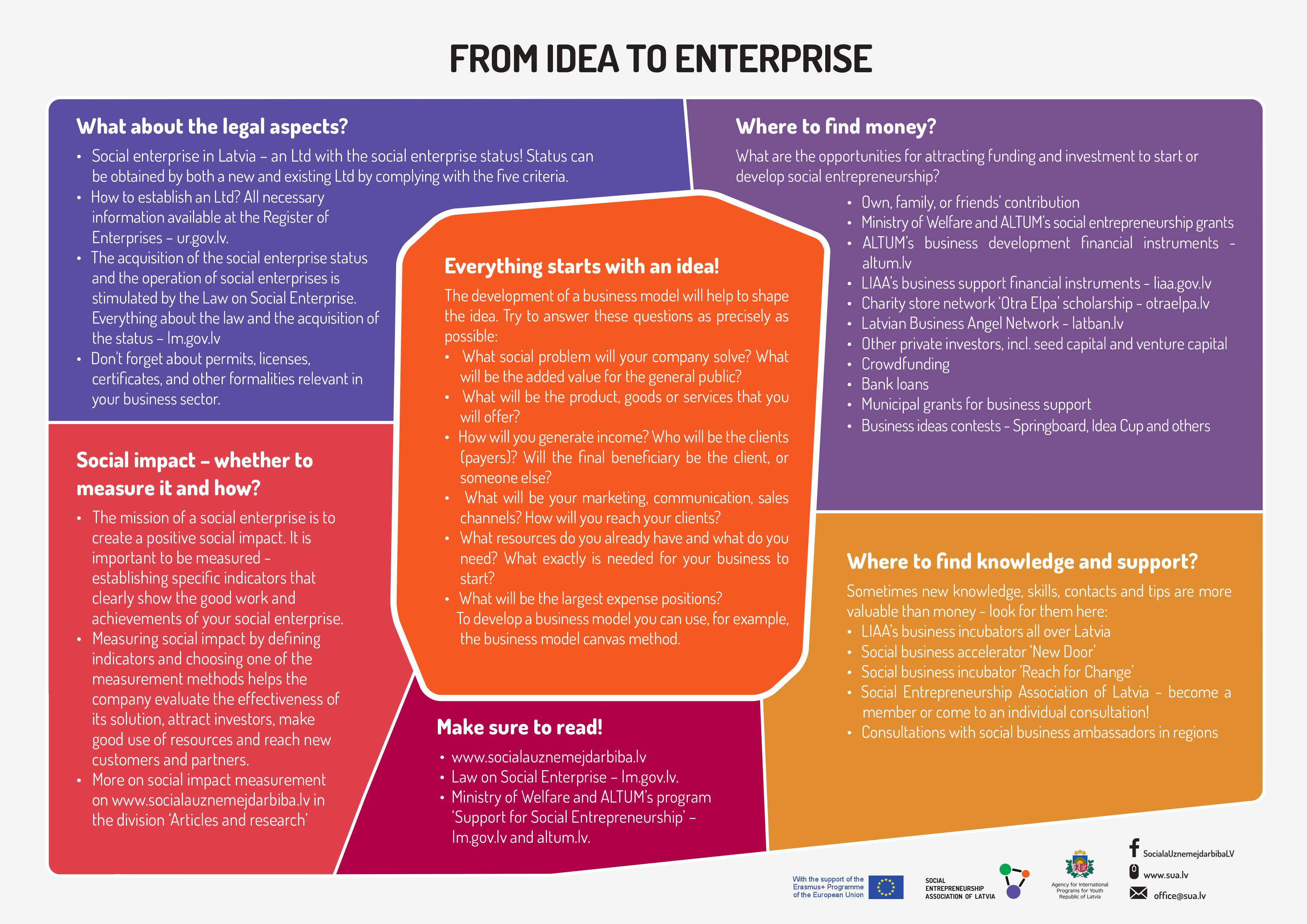

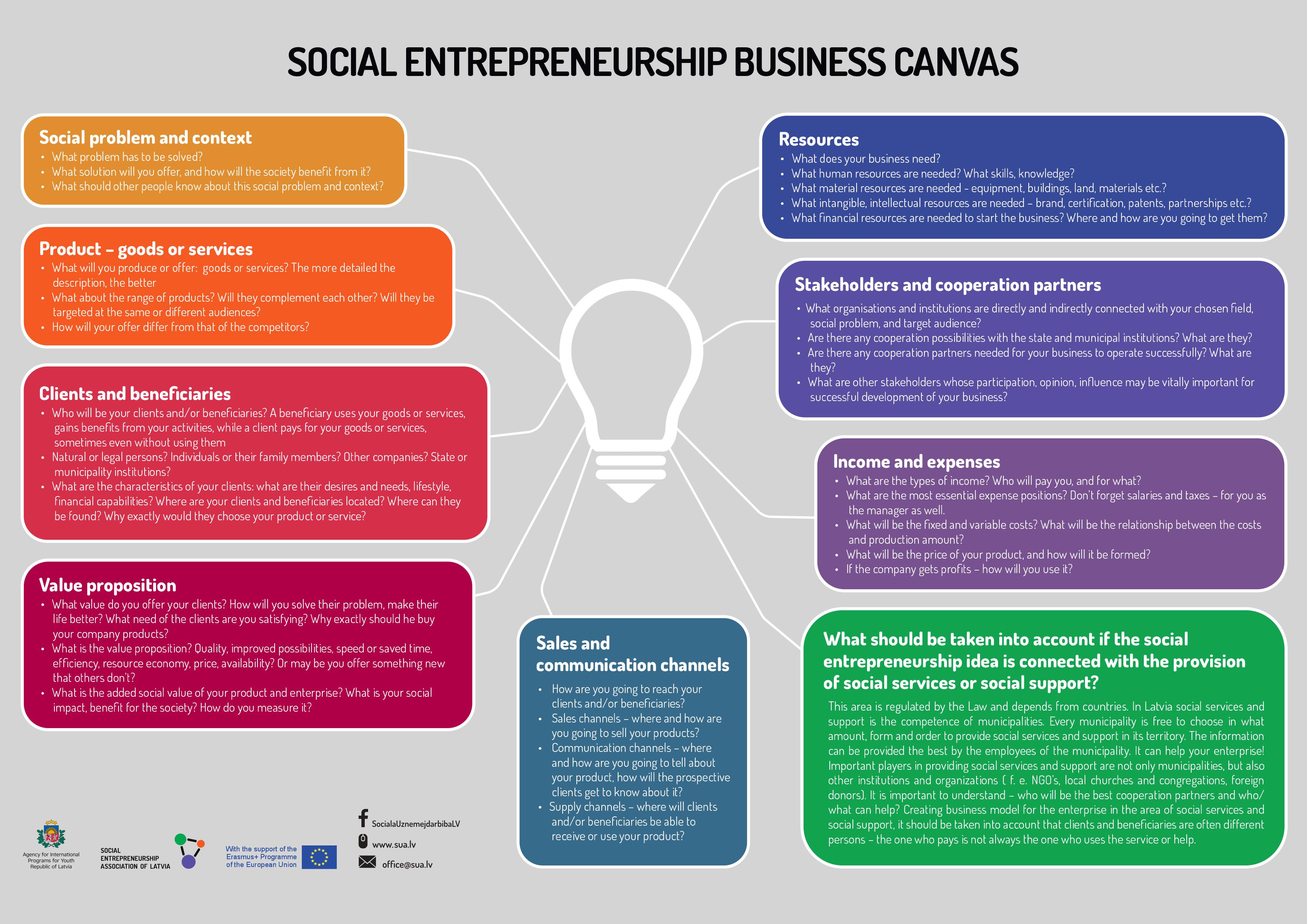

Social entrepreneurship: from idea to enterprise

How to start your enterprise? Info material "From idea to enterprise" may help you!

10 questions about social entrepreneurship

Still have question about social entrepreneurship? "10 questions about social entrepreneurship" may help you!

Who we are

NGO "Social Entrepreneurship Association of Latvia" (SEAL) is a member organization to promote the development of social entrepreneurship in Latvia. We bring together like-minded organizations, companies and people who believe that social entrepreneurship in Latvia has huge potential and who are ready to participate in the development and strengthening of the sector.

The SEAL was founded in autumn 2015 and five its founders are the Foundation for Open Society DOTS, the Social Research Center PROVIDUS, the Latvian Samaritan Association, the charity store network ‘Otra Elpa’, social business accelerator ‘New Door’. They are organizations that had done a great deal in the field of research and promotion of social entrepreneurship even before, as well as the ‘pioneers’ of social entrepreneurship in Latvia, who have proved with their work that social entrepreneurship in Latvia is necessary and possible. The SEAL currently has more than 90 members - full list and short descriptions can be viewed HERE.

WHAT WE DO?

The association operates in three main directions:

1. Advocacy of interests at local, regional and national levels. The SEAL participated in the development of the Law on Social Entrepreneurship, our representative is currently in the Commission for the Status of Social Enterprises at the Ministry of Welfare. The SEAL also focuses its attention on social entrepreneurship opportunities at the Latvian level, as well as participates in the development of a social entrepreneurship support program. We also work with other regional and national decision-makers and policy-makers to create a supportive environment for social entrepreneurship in Latvia. Our cooperation network includes municipalities, entrepreneurship support organisations, local, regional and national stakeholders.

2. Improvement of the capacity of members, development of the experience and knowledge-sharing platform. In various ways, we help our members to achieve better their goals by providing joint activities, fast and effective information exchange, up-to-date information on finance and cooperation opportunities, and counseling support. We promote the goods and services of our members in various ways, for example by collecting information about the member’s offer, organizing the Social Entrepreneurship Market in the Kalnciems Quarter, and introducing with useful partners.

3. Informing society about social entrepreneurship. The SEAL takes part in various events to inform the wider community about the opportunities offered by social entrepreneurship. We have created a network of social entrepreneurship ambassadors in the regions of Latvia, we regularly participate in the events organized by our ambassadors. Every year we organize the industry’s largest and most ambitious event - the Social Entrepreneurship Forum. We maintain the largest source of information in the Latvian language about social entrepreneurship - www.socialauznemejdarbiba.lv.

OUR TEAM

The daily work of the association is managed by SEAL team: director Regita Zeiļa, project manager Līva Švarce, project manager assistant Māra Skuja and event coordinator Līga Ivanova.

The Association’s Council consists of five people elected by the members for a term of two years. The Council acts as the strategic advisory body of the Association, defining the main directions of the SEAL, as well as voting for the admission of new members of the SEAL. The Council meets not less than once a quarter.

Composition of the Association’s Council (of date until November 23, 2021)

Andris Bērziņš, Chairman of the Association ‘Latvian Samaritan Association’

Inga Muižniece, Head of social enterprise “SONIDO”

Elīna Novada, Head of social enterprise “Svaigi.lv”

Agnese Frīdenberga, think-tank “Providus” researcher

Miks Celmiņš, Head of “Make Room Europe”

Business details

Association “Latvijas Sociālās uzņēmējdarbības asociācija”

Reg.No. 50008244721

Legal address: Alberta street 13, LV-1010 //

Swedbanka // LV35HABA0551040981984

Achievements

Since the foundation in the autumn of 2015, the Social Entrepreneurship Association of Latvia has become one of the leading organizations in the social entrepreneurship sector in Latvia, not only taking care of improving the capacity, knowledge, and skills of its members in various ways but also developing and promoting the overall social enterprise ecosystem in Latvia.

The most important accomplishments of the Association, which have significantly contributed to the development of the social entrepreneurship sector in Latvia:

- As a result of the three years of work and active involvement of the Association, the Latvian parliament Saeima unanimously adopted the Law on Social Entrepreneurship at the end of 2017, which came into force on 1 April 2018. The law, for the first time in Latvia, defines a social enterprise and the legal framework for its activities.

- The participation of the representative of the Association in the Commission on the Status of the Social Enterprise of the Ministry of Welfare provides a professional and experienced expert opinion during the status award process.

- Active participation in the development of a financial support program for social entrepreneurship of the Ministry of Welfare and ALTUM, ensuring the representation of the interests and needs of social enterprises, as well as a clear explanation of the possibilities and conditions provided by the program.

- Local governments in Latvia are aware of social entrepreneurship and its opportunities; more than 20 municipalities have been involved in activities to promote social entrepreneurship in their territories, together with British Council Latvia we have created a useful toolbox for municipality representatives and tested support mechanisms for social enterprises in 3 municipalities - Ogre, Rēzekne and Līvāni

- Business incubators and the employees of Investment and Development Agency of Latvia are informed and educated about social entrepreneurship, its nature and possibilities, as a result, the business incubators are open to social enterprises and are able to offer them appropriate support.

- Through active work, meetings and communication with other public and private actors, social entrepreneurship has become a topical and stimulating issue for various state and local government institutions (e.g., the State Employment Agency, International Youth Program Agency, etc.), banks, private investors, companies, etc.

- The topic of social entrepreneurship and social enterprise stories have been promoted in the media, including the biggest online press releases of Latvia (Diena, NRA, Latvijas avīze), on television (LTV, LNT, TV3), radio (LR1, LR5, LR6, Star FM), online portals (lsm.lv, DELFI, TVNET) and others.

- The Social Entrepreneurship Forum of the Association has become the most important annual event of the social entrepreneurship sector, bringing together more than 160 participants, lecturers and experts from Latvia and abroad. Resultant to the forum, a new audience was introduced with the topic of social entrepreneurship and valuable long-term relationships established.

- Every year the Social Entrepreneurship Catalogue of Latvia is published, introducing the Latvian and international audience with the success stories of Latvian social entrepreneurs.

- A network of Social Entrepreneurship Ambassadors has been established together with British Council Latvia, with more than 20 active creative community leaders in all regions of Latvia. Through the network of ambassadors, more than 3,600 people across the country have been informed about social entrepreneurship.

- Three international publications on various social entrepreneurship topics have been published, which are available free of charge at www.socialauznemejdarbiba.lv and have been proactively introduced to decision-makers and opinion leaders throughout Latvia.

- Through the ‘one-stop-shop’ consultations, more than 50 people have acquired the necessary knowledge, skills and information to implement their social entrepreneurship ideas.

- More than 100 educational and informative events throughout Latvia have been implemented, providing accessible and comprehensible information on social entrepreneurship opportunities in all regions of Latvia.

- Creation and maintenance of the largest and most comprehensive internet resource in Latvian on social entrepreneurship www.socialauznemejdarbiba.lv.

- Every year the Social Entrepreneurship Market is organized in cooperation with the Kalnciems Quarter - this event not only provides for the visibility of social enterprises but also informs the new audiences about social entrepreneurship.

- Together with the Association members and partners, especially the British Council of Latvia, we create a community to exchange social entrepreneurship knowledge and experience, as a result, new and productive cooperation and opportunities are available for Latvian social enterprises.

Do you want to join our work and engage in creating a social entrepreneurship environment while also using the diverse opportunities and privileges offered by the Association? Become a member! More information here.